In April 2019 I had the pleasure of leading the Shire of Roxbury Mill team at Revenge of the Stitch, a 24-hour sewing competition. After consulting with our model, Ava Deinhardt, we settled on a 12th-century bliaut. I was particularly interested in bliauts, as they’ve been finicky to pin down, and I happen to know Dr. Monica L. Wright, an expert on bliauts, and I wanted to apply her research.

After several requests for our team’s documentation, I am posting it here. You can also download a PDF copy.

Documentation

Contents

- The Model and Garments

- The Team

- Garments

- Bibliography

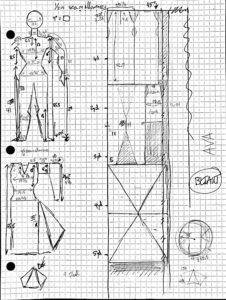

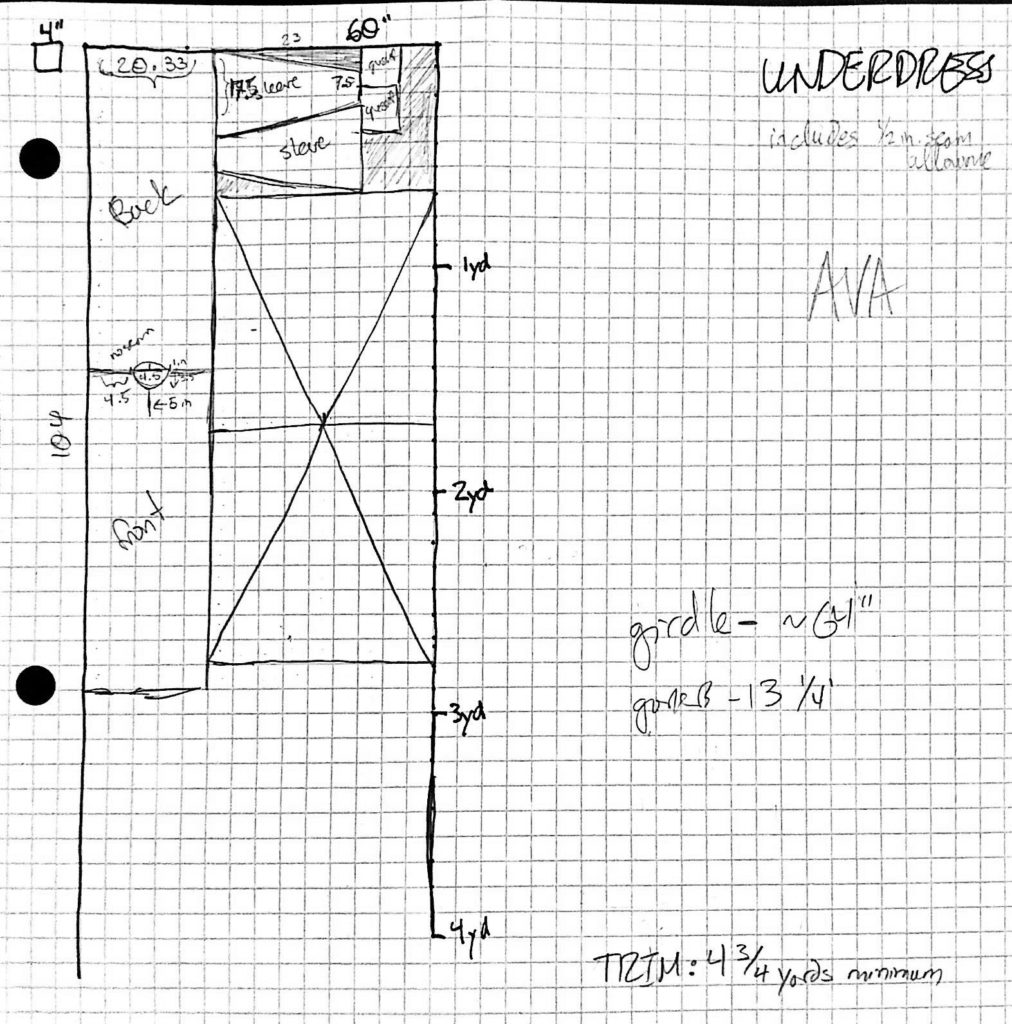

- Appendix A: Pattern Drafts for Bliaut and Underdress

The Model and Garments

In the Shire of Roxbury Mill, we use Revenge of the Stitch to make sure our most dedicated new members have court-worthy garb. M’lady Ava Deinhardt has distinguished herself through exploration of many of the activities in the SCA, including heavy combat, woodworking, and the scribal arts, and will soon be fought for during Spring Crown. As such, m’lady Ava is in need of garments worthy of a potential princess. Thus, we proposed a silk-trimmed bliaut and underdress in her colors of black, white, and blue. Further, we determined that she would need a long-wearing leather girdle and pouches suitable to a noblewoman who is actively engaged in her estates. Finally, because m’lady Ava has a great love of the outdoors (and because she has not yet been raised to the nobility), we determined that an appropriate, non-presumptuous headpiece would be a chaplet (flower crown). The nature theme has been followed through in an oak clasp on her underdress and an acorn decoration upon her belt.

The Team

The Roxbury Mill team is comprised of six members and a model from the Shire of Roxbury Mill. Five of the six members of the Roxbury Mill team and our model have been in the SCA for less than four years.

Lady Elenor de La Rochelle alias Ela is the team lead as well as the lead on the bliaut. She drafted the patterns for the bliaut and underdress, and it is her first time drafting a pattern for someone else. This is her second time competing at Revenge of the Stitch. She would like to thank Baroness Ysabeau ferch Gwalchaved for her mentorship during preparation.

Lady Adelaide Half Pint is the lead on the chaplet and veil. She drafted the pattern for the veil. It is her second time competing at Revenge of the Stitch.

Lord Gabriel of Hitchen is the lead on the hose. It is his first time making hose, hand-sewing an entire garment, sewing for someone else, and competing at Revenge of the Stitch. Indeed, Lord Gabriel only learned to sew in the last year; he learned to hand sew in the last few months in preparation for this competition.

Baron Hamish MacLeod is the cordwainer for the team. He has challenged himself to use less expedient but more authentic techniques in his work this year, using a stab awl and natural fiber sewing threads. It is his second time competing at Revenge of the Stitch.

Lady Kaaren Valravn is the lead on the underdress. She has only made two outfits before; it is his first time sewing completely by hand, sewing for someone else, and competing at Revenge of the Stitch. Lady Kaaren has been in the Society for less than a year.

Lady Lucy of Wigan is the lead on the bliaut trim. She learned to weave on a rigid heddle loom in February and learned to inkle weave in March specifically for this competition. This is her third time competing.

Ava Deinhardt (non-sewing model) has been in the Society for less than a year.

Garments

Bliaut

What Is a Bliaut?

The bliaut is a noble garment fit for both men and women, with the women’s garment being popular from the mid-12th century through the early 13th (Burnham; Wright, “The Bliaut,” 61 and 65; Wright, Weaving Narrative, 41 and 47). Structurally, the bliaut is a difficult garment to create, as there is little information about how the garment was constructed and worn. This was why the team was attracted to making one. In developing Ava’s bliaut we wished to figure out the most appropriate fabric, if there were pleats and lacing (and where they should go), and if there should be an attached, pleated skirt.

When interpreting the construction of garments is difficult, the best choice is to return to period exemplars, such as illuminations. For this garment, our primary exemplars were Figure 1 (the Ecclesiasticus Initial from the Winchester Bible) and Figure 2 (the daughters of Job in Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Latin 15675). But what fabric should we use? And what should we do about the sculptures in Chartres Cathedral that keep popping up every time we search for “bliaut” (Fig. 3)? These sculptures depict a garment that has been labelled as “bliauts,” but their finely pleated skirts are dramatically different from most other depictions of bliauts. Thankfully, French literature and medieval clothing scholar Monica L. Wright (Professor and Granger & Debaillon Endowed Professor of French at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) closely analyzed the word bliaut in period usage and scholarship. She determined that Eugène Viollet-le-Duc misapplied the term “bliaut” to the Chartres Cathedral figures in the 19th century (Wright, “The Bliaut,” 61-62, 77, and 79). This mislabeling unfortunately resulted in much confusion in how to construct an authentic bliaut. Indeed, many online patterns (e.g., Sunneva de Cleia, Pitcher, and Stouten) have struggled to reconcile the apparent conflicting types of bliauts. Once Lady Ela’s research uncovered that the Chartres Cathedral sculptures were not true bliauts, the apparent conflict was resolved and Lady Ela was able to move forward to design m’lady Ava’s bliaut by following the smoother lines of the illuminated garments. While Lady Ela reviewed the aforementioned patterns during her research, she ultimately determined that she needed to draft a pattern from scratch based on the exemplars and Wright’s analysis.

Our research led to several other guiding conclusions. First, the bliaut is a single-piece garment as it is described as being put on as one piece in Chrétien de Troyes’ Erec et Enide (Wright, “The Bliaut, 68). Secondly, the bliaut was fitted and probably laced: laces are mentioned in Marie de France’s Guigemar and Lanval, while tightening is referred to in Erec et Enide (Wright, “The Bliaut,” 68-69 and 75; Wright, Weaving, 119). Robin Netherton suggested that the lacing was probably in the side (paraphrased by Wright, Weaving, 26); Figure 1 shows wrinkles that would correspond with side-lacing. Thirdly, it was probably gored, as there are multiple instances of bliauts being described as gironé (Burnham; Wright, “The Bliaut,” 75). Finally, the twelfth century had perfected the technique of “dividing a rectangle of cloth” without wastefulness, which meant that any pattern should keep curved shaping to a minimum (Crowfoot et al. 177). Appendix A shows how Lady Ela incorporated these conclusions into our working pattern.

The Materials

Silks are the most commonly referenced fabrics in conjunction with bliauts, and plain tabby-woven silks have been found in the London digs (Crowfoot et al. 89; Wright, “The Bliaut” 74). Because m’lady Ava’s colors are black, white, and blue, we decided to go with a black silk bliaut. A black silk bliaut is mentioned in Chrétien de Troyes’ Le Conte de Graal, while a tight bliaut of dark silk was mentioned in Béroul’s Tristan (Wright, “The Bliaut,” 69-70 and 77). Figure 4, of the Virgin Mary, is also a contemporaneous illumination containing a black overdress. In dyeing, black could be achieved by mixing madder with woad or indigo (Crowfoot et al. 200).

Many bliauts were lined with white ermine (Wright, “The Bliaut, 66; Wright, Weaving, 47). Due to the hot and variable Atlantian weather, we chose to substitute a white silk lining into just the sleeves: no weasels or wallets were harmed in the making of this bliaut.

The entire garment is sewn with white silk thread, which was commonly used on silk and upper-class garments (Crowfoot et al. 152). Finally, the side-lace cording is cable-spun by Lady Ela out of silk.

Bliaut Trim

Our trim, woven by Lady Lucy, is a warp-faced tabby weave woven on an inkle loom. Warp-faced narrow bands (narrow wares) date back to the Iron Age in the form of tablet weaving (Crowfoot et al. 130; DeGarmo). By the 12th century, narrow wares could be created by tablet weaving, fingerloop braiding, other braiding, or tabby weaving (Crowfoot et al. 130). A warp-faced (unbalanced) tabby weave can be achieved with a rigid heddle loom or box loom, but it can also be achieved with tablets by only threading two holes per tablet. As a new weaver, Lady Lucy is using modern inkle looms. The inkle loom is a more recent invention, dating to somewhere in the 17th or 18th centuries, but it achieves the same result as a period loom (DeGarmo).

Lady Lucy is using 20/2 silk for both the warp and weft. By the seventh century, silk was the preferred material for narrow wares (Crowfoot et al. 130). The white-and-blue pattern is a simple check in m’lady Ava’s colors chosen to complement the black bliaut. It was drafted with the assistance of Baroness Ysabeau and The Weaver’s Inkle Pattern Directory by Anne Dixon.

Underdress

Pattern Consideration

Figure 2, as well as figures wearing bliaut-type garments in the Hunterian Psalter and St. Albans Psalter, all have tight fitted sleeves peeking out from beneath the long-cut sleeves of the bliaut (also noted by Monica Wright, Weaving, 24, who adds that it could be wool or linen). While Wright calls these a chainse, The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant calls it a cote (Thursfield 76-83). This would not have been a woman’s underwear; rather, it is an intermediary layer between the outer layer and the underwear layer. As an intermediary layer, this dress may have been cut looser than the bliaut, as the bliaut’s structure would fit the underdress to the body. Based on the exemplars, The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant, and the twelfth-century technique minimal-waste cutting mentioned in Crowfoot, et al., Lady Ela drafted an underdress that is cut comfortably in the body (see Appendix A). In keeping with the exemplars, the sleeves are cut tight and sewn shut.

The Materials

M’lady Ava’s underdress is of a blue linen, inspired by both her colors and figure 4, which shows the Virgin Mary with a blue underdress. While depictions of religious figures are often standardized, and therefore not always reliable for the cut of clothing, this image demonstrates that the color combination was conceivable within period. While linen is not the easiest fiber to dye, and while linen was primarily reserved for underclothes, linen could have been worn visibly as in an intermediary layer, as linen was a common fabric (Crowfoot et al., 18-19). Furthermore, woad dye has been attested to during this time (Crowfoot et al., 19 and 200). However, linen quickly degrades in damp conditions, and most dyes are difficult to determine without advanced analysis (often requiring at least some damage to the item). Despite this, with linen and woad both being available during our period, blue linen is not out of the realm of possibility. More importantly, Atlantian weather is quite changeable, and because we do not wish to fry our model, we have thus opted for a linen layer!

Hose

M’lady Ava’s hose are cut on the bias of a natural black-and-white 2/2 twill wool. This fabric replicates period wool, which could be patterned by mixing natural undyed shades, such as black and grey (Crowfoot et al. 15-18). Our wool is a light 2/2 twill; 2/2 twills date to the Iron Age, while 2/1 twills are attested to by 1151 (Crowfoot et al. 36 and 27). By the twelfth century, hose were probably being cut on the bias to improve fit and were often made of wool (Crowfoot et al. 187; McGann). While only running stitch has been attested to in the London digs, Crowfoot, et al., hypothesize that backstitch was used on bias-cut hose for greater strength (156). Lord Gabriel adapted Ava’s hose from the “Cloth Hose” pattern by Kass McGann. McGann’s pattern closes matches finds from the London digs (Crowfoot et al. 185-190). As with women’s hose in period, Ava’s hose reach roughly to her knees (Crowfoot et al. 186). We have substituted cotton for the usual linen thread (Crowfoot et al. 151). In keeping with research and to maximize the structural integrity of the hose, Lord Gabriel will be hand sewing the hose using the backstitch.

Veil and Chaplet

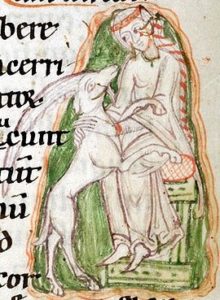

While a bliaut is a high-ranking garment and often worn with a crown, m’lady Ava has yet to be raised to the nobility. Therefore, we chose to give her a crown that could be worn by women of any rank: a chaplet, or flower crown (Carruthers; Courtais 17; Gilbert). The English word “chaplet” is a loan from Old French “chapelet,” both meaning a headdress and usually a flower crown; the term entered English somewhere between 1066 and 1300. Figure 5, which depicts a woman wearing a bliaut-type garment with tight sleeves, is glossed as “Unicorn and Virgin – Unicorn with feet on lap of virgin, wearing wreath, seated on a cushioned bench.” While the woman’s chaplet uses colored flowers, Lady Adelaide is making Ava’s chaplet out of white flowers to match the garments. It is unclear how the flowers would have been bound together; complex interweaving of stems, twine, string, or wire are all probable. Lady Adelaide is using wire for long-lastedness, in the hopes that the chaplet shall last until May Crown (the weekend after Revenge of the Stitch).

Often, twelfth century ladies wore two long braids with the bliaut. However, m’lady Ava prefers to leave her hair loose beneath her veil, which is an appropriate style in period for both young women and queens (Courtais 17). The veil is cut in an oval, as is seen in illuminated exemplars of the period (for example, the Virgin Mary in Figure 4 wears either an oval or circular veil). Ava’s veil is cut from sheer white linen and sewn with cotton thread.

Cordwainery

Baron Hamish was challenged by the team to create leather accessories for an 11th to 12th century noblewoman appropriate for everyday wear with a bliaut. The team requested a long double-wrapped girdle and garters, but left the kind of belt pouches and accessories up to the resident expert.

Girdle and Garters in Period

In the Middle Ages, leather of any sort was a high-status material both for clothing and accessories, as well as for industrial and agricultural applications. Therefore, a leather belt would represent a substantial expense. A cordwainer or leatherworker would work hard to avoid waste of any kind while cutting and trimming his hides. Belts, especially long belts, would have rarely been all of one long strap. In fact, many belts required splicing and joining with stitching and/or metal findings. Buckles of higher status belts were most often riveted onto the strap with a buckle plate rather than slotting the strap and sewing the buckle directly into the belt. A matching strap end was often added as well. Garters were basically smaller belts with buckles sewn in without buckle plates. Most of the surviving examples of these civilian buckles are cast brass, bronze, gilt brass/bronze, silver, silver gilt and, rarely, gold.

Pouches

Since people first needed something to hold loose items, pouches and bags have existed in one incarnation or another. The belt pouch is first seen in Europe during the Bronze Age; bag-like or pouch-like elements of animal hides or pieced leather cut to a similar form and sewn together have been found in bog burials, middens, and excavations in non-acidic soils. While there were undoubtedly pouches and belt pouches earlier, relatively few surviving exemplars have been unearthed to reflect that. Unfortunately, the predominance of leather finds in archaeological records relates to shoes, military items and horse tack.

Since people first needed something to hold loose items, pouches and bags have existed in one incarnation or another. The belt pouch is first seen in Europe during the Bronze Age; bag-like or pouch-like elements of animal hides or pieced leather cut to a similar form and sewn together have been found in bog burials, middens, and excavations in non-acidic soils. While there were undoubtedly pouches and belt pouches earlier, relatively few surviving exemplars have been unearthed to reflect that. Unfortunately, the predominance of leather finds in archaeological records relates to shoes, military items and horse tack.

The pouches that Baron Hamish will make for m’lady Ava are a very early “escarcelle” or kidney-shaped belt pouch and an “almoniere” or alms pouch. Both are from designs that first appear in the 11th century and that persist in recognizable ways through to the 14th century. They were chosen as being quintessential daily wear items and for patterns that can be scaled up and embellished as needed by the cordwainer.

Leather Processing in Period

During this period, leather was tanned to prevent decay and to create a material that was durable, flexible (in most applications), and reasonably protective. Several chemicals were used as a part of the process, chiefly urine, which acted as both a solvent and a re-agent for the other elements of the process. Salt, soap, brains, chopped oak bark, alum, bird guano, and even dog feces all had their part to play, depending upon the end finish and (some of) the desired color. The tannage bath was mixed by hand and foot with water, usually in large vats. Multiple types of hide/leather products were available in period:

- Rawhide required little or no chemical treatment of the hide other than to remove hair. Parchment/vellum falls in this category, but the physical treatment can be extensive.

- Mineral tannage in period would have primarily been alum tawing, which produces a soft, stretchy, and snow-white leather. Due to its poor resistance to water when not combined with other tannages, this leather would probably have been used more for indoors applications in temperate climes. Not widely available today, it is still used in conservation bookbinding because of its long-term stability. Alum tawed leather is a poor choice for military applications (except perhaps in very dry climates) as the alum tends to be poorly fixed and is easily washed out if the leather becomes wet.

- Vegetable tannage, strictly speaking, is the only form of true tanning since it uses tannin leeched from vegetable matter. Contrary to popular conception, a wide variety of leaves and barks were used to perform this task, not just the commonly-quoted oak bark. The vegetable-tanned leather commonly available today is made specifically for tooling, but this is not necessarily the only form vegetable-tanned leather can take.

- Oil tannage or chamoising is produced through the oxidation of oils that are applied to the hide. The leather tends to be flexible and readily absorbs and expresses water. Today, chamois is one of the few true oil-tanned leathers still available. In period, heavy oil-tanned leathers would have been available. Brain and buck tanning are forms of oil tanning. Some leathers marketed today as “oil tanned” are not and are merely vegetable- or chrome-tanned leathers impregnated with oil and/or wax to make them water resistant.

Most modern forms of chemical tanning are not period, but rather a development of the 19th century.

In terms of colors, earth tones and colors related to natural leather were the most common. The paler or darker the hide, the more variation in the shades of the finished leather. White leather appears to have almost exclusively of non-bovine origins: sheep, goat, rabbit, cat, and dog skins were all used by the “tawer” or “whitawer.” The origins of “saddle tan”, “British tan”, and “Cordovan” leather all have their genesis here. Custom colors were fairly rare, as analine dyes were nonexistent in period, and few period dyes were color- and light-fast enough to dye leather with. Two exceptions to this were the deep red of Morocco leather (requiring a heavy, long soaking in a sumac dye bath) and vinegaroon black (iron, acid dying).

The Materials

The selected leathers are an oak-tan cowhide in thicknesses of 4-6 oz./sq. in. and 7- 8 oz./sq. in. and 3-5 oz. soft tan deerskin. Neither of these products are tanned in the period process. Rather, they are produced as commercial products using the correct chemical equivalents of the ancient tannages (much to the relief of Baron Hamish’s wife and neighbors, who thank him for not attempting to tan hides in the yard).

Bibliography

Primary Sources for the Garments

- Béroul. Tristan.

- Chartres, Chartres Cathedral.

- Chrétien de Troyes. Erec et Enide.

- Chrétien de Troyes. Le Conte de Graal.

- Glasgow, Glasgow University Library, Sp Coll MS Hunter U.3.2 (229) (Hunterian Psalter).

- Hildesheim, St. Godehard Dombibliothek, St. Albans Psalter.

- London, British Library, Cotton MS Nero C IV (The Winchester Psalter.

- Marie de France. Guigemar.

- Marie de France. Lanval.

- New York, Morgan Library, Morgan MS M.0832.

- Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Latin 15675

- Winchester, Winchester Cathedral, Winchester Bible.

Secondary Sources for the Garments

- Burnham, Micaela (Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia, Meridies). “The Bliaut Revisited.” House Wild Rose, https://housewildrose.weebly.com/the-bliaut-revisited.html

- Carruthers, Emilie. “The Ancient Origins of the Flower Crown.” The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty, 4 May 2017, http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/the-ancient-origins-of-the-flower-crown/

- Crowfoot, Elisabeth et al. Textiles and Clothing 1150-1450. Medieval Finds from Excavations in London 4, Boydell Press, 2001.

- De Cleia, Sunneva. Mistress Louise de la Mare’s Bliaut, 22 Feb. 2017, http://atlantasca.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Bliaut-Instructions-2017.pdf

- de Courtais, Georgine. Women’s Hats, Headdresses and Hairstyles, Dover, 2006.

- DeGarmo, Tracy. “Inkle Weaving in History.” Inkleweaving.com, 2000-2005, http://www.degarmo.net/inkle/notes/history.html

- Dixon, Anne. The Weaver’s Inkle Pattern Directory, Interweave, 2012.

- Gilbert, Rosalie. “Headwear of the Middle Ages.” Rosalie’s Medieval Woman, https://rosaliegilbert.com/headwear.html

- McGann, Kass. Reconstructing History – RH001—Cloth Hose. Sewing pattern.

- Pitcher, Izabela. “12th Century Dress – the Bliaut.” A Damsel in This Dress, 28 Apr. 2014, https://adamselindisdress.blog/2014/04/28/12th-century-dress-the-bliaut/

- Stouten, Esther. “12th Century The Bliaut.” Historical Costumes, 2006?, https://historicalcostumes.nl/The_High_Middle_Ages_bliaut.php

- Thursfield, Sarah. The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant, Ruth Bean, 2001.

- Wright, Monica. “The Bliaut: An Examination of the Evidence in French Literary Sources.” Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol. 14, 2018, pp. 61-79.

- Wright, Monica. Weaving Narrative: Clothing in Twelfth-Century French Romance, Penn State UP, 2009.

Sources for Cordwainery

- Allin, Clare E. The Medieval Leather Industry in Leicester. Leicestershire Museums, Art Galleries and Records Service, 1981.

- Black, W. H. History and Antiquities of the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers of the City of London, privately printed, 1871.

- Cherry, John. “Leather.” English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques & Products, edited by John Blair and Nigel Ramsay, The Hambledon Press, 1991.

- Churchill, James E. The Complete Book of Tanning Skins and Furs, Stackpole Books, c1983.

- History Review, vol. 13, 1960.

- Reed, R. Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers. Studies in Archaeological Science, Seminar Press, 1972.

- Vivian, June. Home Tanners’ Handbook, A. H. & A. W. Reed, 1976; Douglas & McIntyre, 1981, c1976.