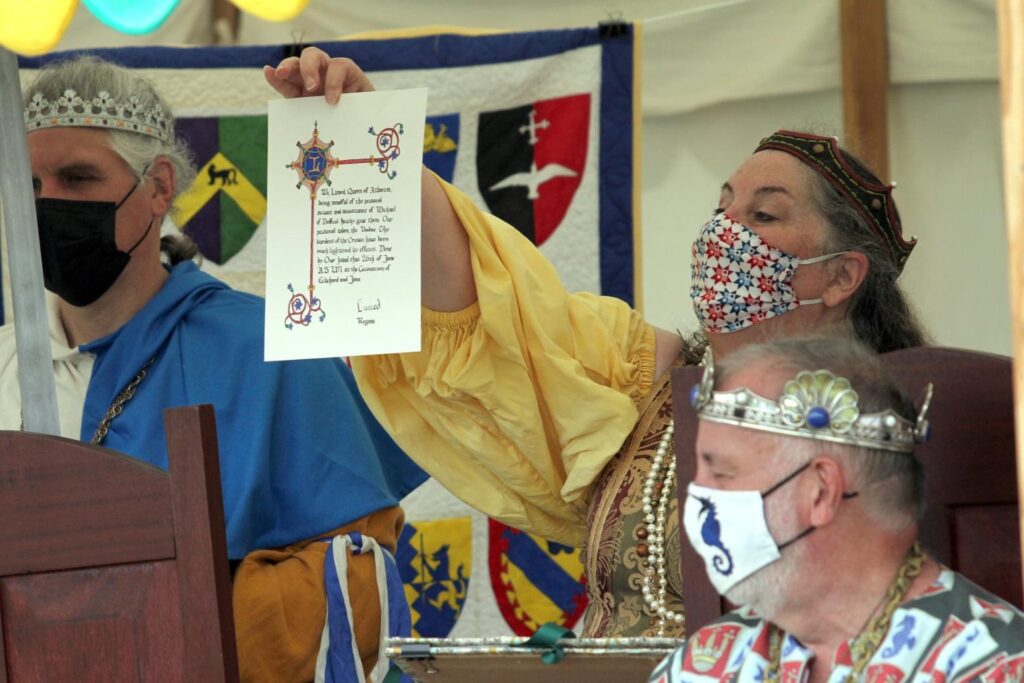

Kolfinna Valravn is one of my favorite people, period. In addition to being an amazing artist, Kolfinna is unfailingly kind, thoughtful, and giving; she thinks of others, and then does something tangible with it. She is always working to make others’ lives better, even when “on a break”. Of course I had to help with her Golden Dolphin (GoA service award).

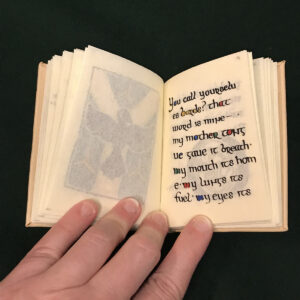

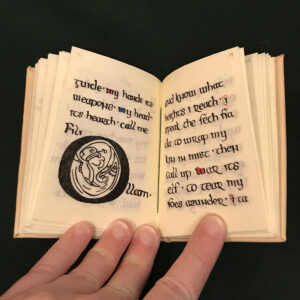

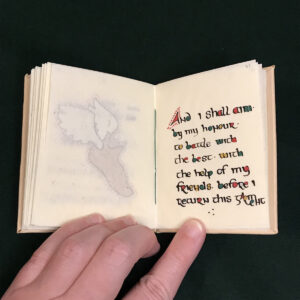

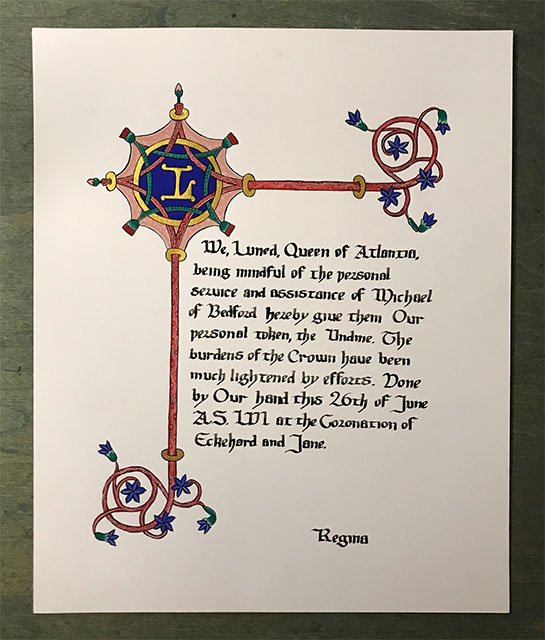

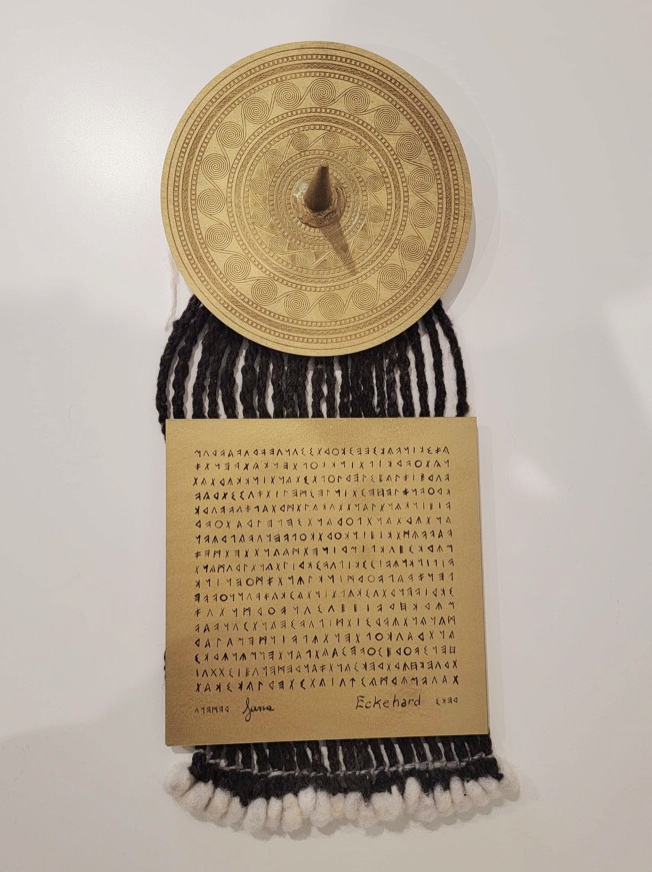

Ollamh Lanea gathered a dream team for this scroll: Bran Mydwynter was our designer, Aurri le Borgne was the “illuminator” (which, in this case, handled substrates, engraving, and assembly), Lanea wrote the beautiful words (of course!), and I was in charge of calligraphy… and spinning and weaving.

Yes. I got to spin and weave for a scroll. Even better: I got to spin and weave for a scroll for Kolfinna!

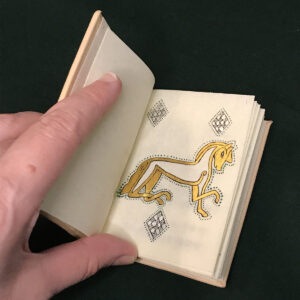

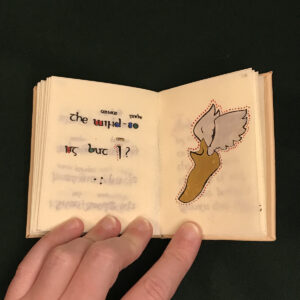

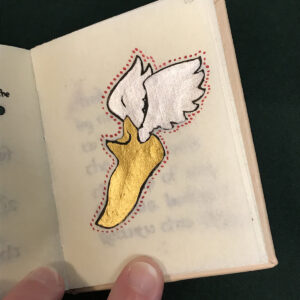

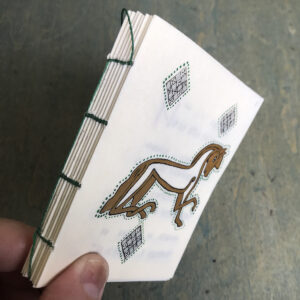

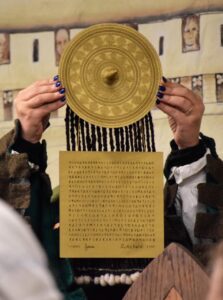

You see, Kolfinna loves the Bronze Age, especially the Egtved Girl. Bran knew this, and designed a scroll that incorporated the Egtved Girl’s spiky belt plaque, corded skirt, and a runic plaque (the research behind the runic translation ALONE is incredibly impressive, let alone the piece as a whole, so please go read about that now).

But first, let’s talk about the calligraphy.

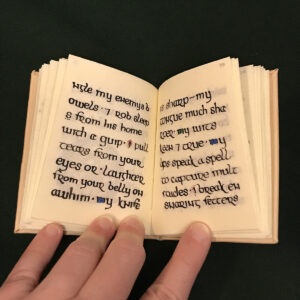

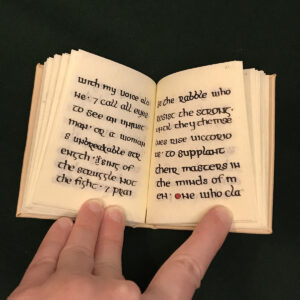

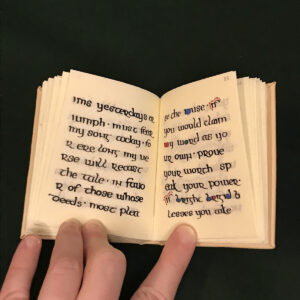

Runic Calligraphy

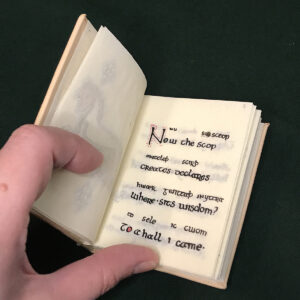

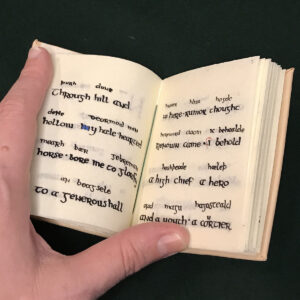

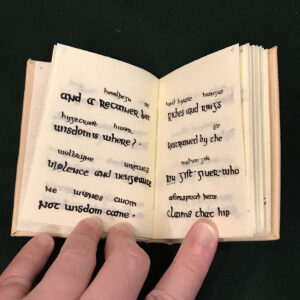

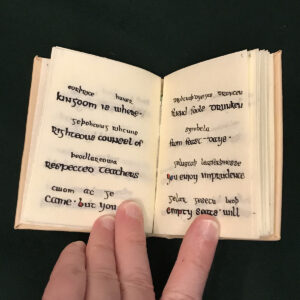

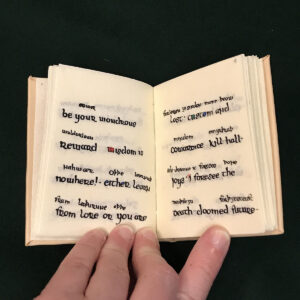

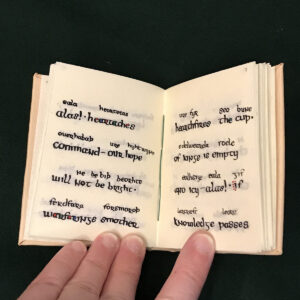

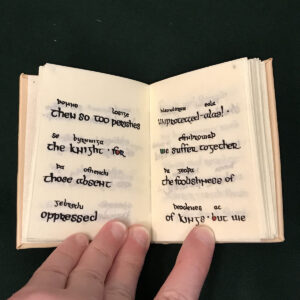

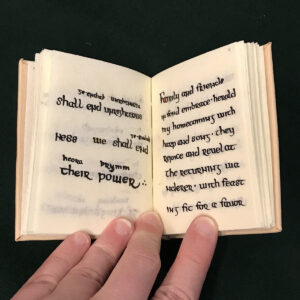

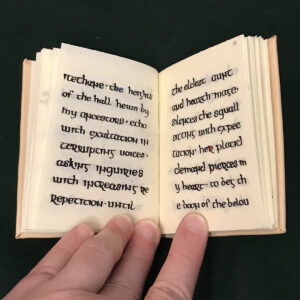

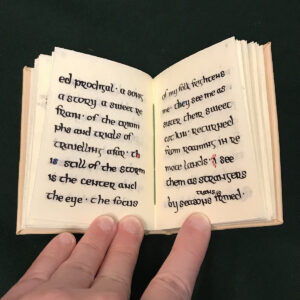

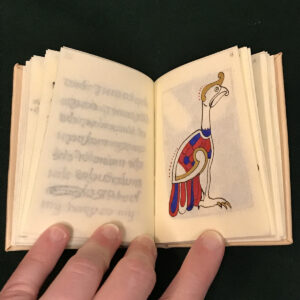

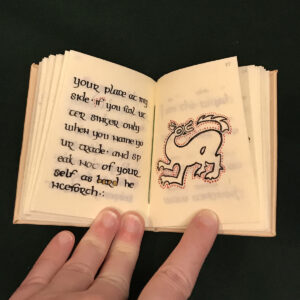

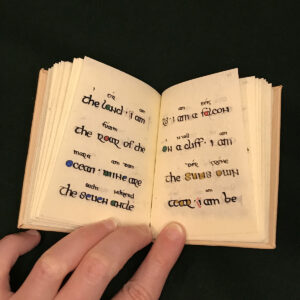

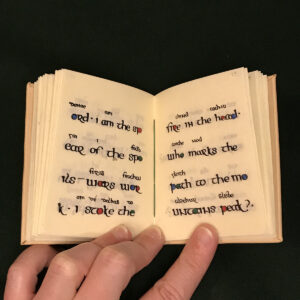

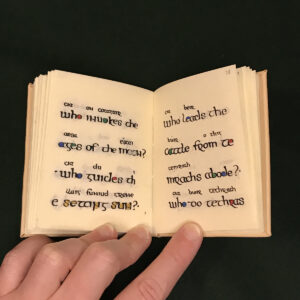

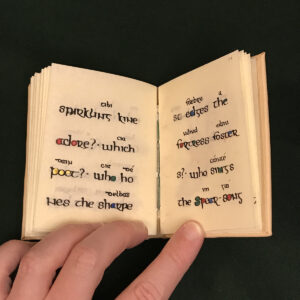

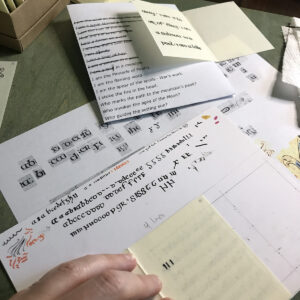

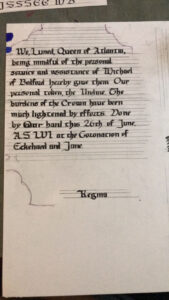

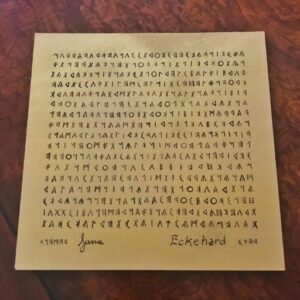

The plaque for the calligraphy was made by Aurri out of a piece of pergamenata attached to thin wood and then spraypainted, giving it an excellent metallic sheen. I had never done calligraphy for a scroll without tracing, so I was incredibly nervous (I hadn’t traced the calligraphy for the Apprentice’s Manuscript, but if I messed up with that I could scrape it or start a new folio if needed). I spot-tested to see if an eraser hurt the base paint, and it didn’t seem to, but I was worried enough about reducing the sheen that I decided to minimize erasing as much as possible. I really didn’t want to freehand this, though, as I was terrified I would mess up the spacing.

Thankfully, Bran had made a layout with the runes that was almost the exact size of the plaque. After discussing with Aurri, I resized it slightly in Procreate to increase the margins so she had more flexibility with attachments when assembling, and then I went old-school carbon-copy-transfer tech: I rubbed the entire back with a pencil, placed it carefully onto the plaque, and then traced over it with a mechanical pencil to transfer the design to the surface.

Since the original runes had fairly regular line weight, being incised, I tried several different tools to paint the runes, including about a dozen different paintbrushes and a tool only known as the dottifier. After some trial and error, I settled on using a crow quill with acrylic paint.

This was incredibly satisfying to do, and I am quite smug about how well it turned out. I also don’t think I can call myself a baby calligrapher anymore.

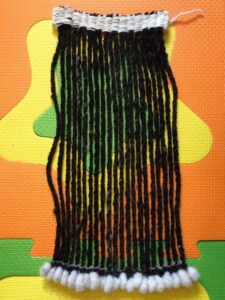

The Skirt

I did the initial research and spinning for an Egtved skirt in 2020 (in fact, I kept bugging Kolfinna with info about it as I was researching and spinning for it), but I’ve been stalled on the actual creation process. However, because of this, I was immediately ready to make a small sampler for the scroll! Because I plan to weave a full skirt soon(ish), I’m not going to go particularly in depth in this section.

While I’ve spun a lot of wool in the last two years, I wanted to spin specially for this project, because I knew exactly the wool to use. Pre-pandemic, Kolfinna joined me at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival for her first ever visit, and she fell madly in love with Jacob sheep (and their two-to-six horns on both sexes). I had purchased a Jacob fleece in 2021, and while the fleece was predominately white (to my disappointment), I thought there may be enough to make the cords of the skirt black. Because I wasn’t quite sure how much yardage I would need, I decided to make the woven base out of white wool; it would be hidden anyway, and extend the amount of wool I had.

Aiming for an 8″-wide sample, I estimated the amount of yarn I needed. I then processed an appropriate amount of wool using wool combs borrowed from Lanea (having washed the fleece last year), then spun up the yarn at ~10 WPI on my wheel. While I was worried about yarn chicken, I actually only used about half the yarn I spun for the skirt sample:

| Estimate | Total Spun | Used | |

| White (warp) | 8 yards + 1 yard plied | 32 yards (7.1 grams) | 16 yards |

| Black (weft & cords) | 101 yards | 114 yards (127 grams) | 62 yards |

| Grey (twining) | 2 yards | 14 yards (1.42 grams) | <1 yard |

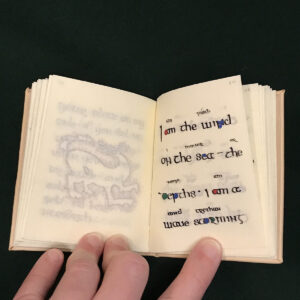

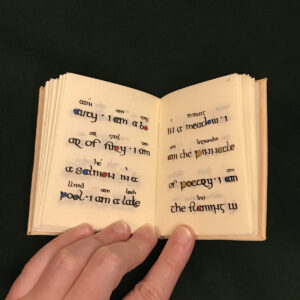

Time for weaving! The Egtved skirt has an interesting construction, where three loops of weft are pulled through and placed on a peg per pass of the warp; as the weaving progresses, two loops are twisted tightly and then plied together into cords. The amazing fiber artist who reconstructed the skirt originally used pegs clamped to a table instead of a loom (which you can see here), but I don’t have a table where I can set up for a long time. Thus, I rigged a semi-portable set-up. I put the warp on my inkle loom, turned my rigid heddle loom upside-down and clamped a peg to its crossbar, and then sat on the floor with my leg between the inkle and the rigid heddle loom. I kept a ruler nearby to make sure that the peg was always 15″ from the warp (especially important to check after taking a break!). As I progressed in the weaving, I plied the cords together using a hand-cranked plying tool to speed the process. As with the original, I tied the ends of each cord in a half-square knot before carrying on.

Once the eight inches were woven, it was time for finishing the bottom of the cords. In the Egtved skirt, the end of each cord has the ends overlapped into a ring, then wrapped with some lightly-felted wool. Instead of combing, I flicked a bunch of white locks, and then threaded the loose locks onto a yarn needle. Using the needle, I threaded the lock through the ends of the loops (to bind them together) before wrapping them around the cords. Instead of wet-felting or friction-felting the ends, I used a modern needle-felting needle (stabby stabby stabby!). Once this was completed, I twined the cords right above these rings with the grey yarn.

Then, I blocked the whole piece. Instead of soaking the piece, I pinned it to the correct length and sprayed it with a squirt bottle, sopping up the extra water with towels. Once it was dry, I wove in all the ends except one, which I left so Aurri could tell the front from the back (as much as there was one).

Then, I blocked the whole piece. Instead of soaking the piece, I pinned it to the correct length and sprayed it with a squirt bottle, sopping up the extra water with towels. Once it was dry, I wove in all the ends except one, which I left so Aurri could tell the front from the back (as much as there was one).

Finally, I wove in all the ends, and passed it off to Aurri with the calligraphed plaque for assembly.

It truly was a fantastic experience to work on this collaboration with Lanea, Bran, and Aurri; it truly was greater than the sum of its parts. The only thing better was Kolfinna’s reaction when she saw it!